Originally published in Business Insider

By Florence Comite, MD

I have no direct insight into the operations of the blood diagnostic company Theranos, and I’ve never met Elizabeth Holmes.

But something clearly went off the rails at Theranos.

The positioning of Holmes as “The Next Steve Jobs” and a $9 billion valuation certainly set her up for a nasty fall.

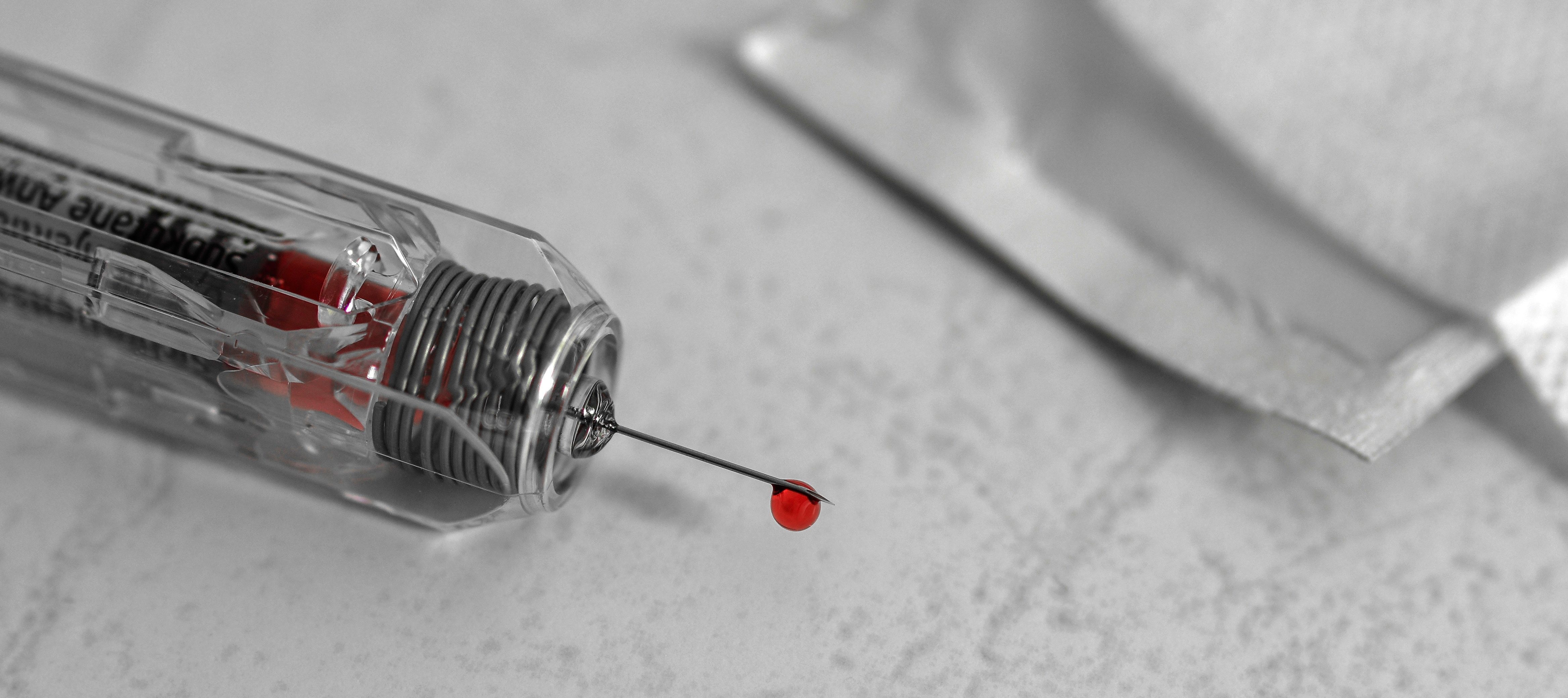

Her idea of doing lab work from a pin prick instead of a blood draw from a vein was meant to help people who are squeamish about needles — and allow for easier access to health data.

If were to get a chance to meet her today, I would seek her side of the story.

Many of her backers still defend her and claim the company is rebuilding its lab.

I want Holmes to have every benefit of the doubt.

Dr. Joel Dudley, a biomedical informatics researcher at the Icahn School of Medicine, Mt. Sinai, published the first and only public data set of Theranos tests versus traditional players such as LabCorp and Quest Diagnostics.

I regularly cite his research that has uncovered new subtypes of diabetes, so it’s no surprise to me that his rigor in his data analysis as a bioinformatics and genomics researcher led him to test the Theranos tests.

Using blood sample lab results in his own, unrelated, research, he wanted to make sure the lab results were accurate – something that would ordinarily come from the clinical chemistry community.

In his research, he found what’s already a well-known frustration in the medical community: lab results have a lot of variability. The same sample can have results that vary from lab to lab, and even within the same lab.

I have personally seen results from conventional labs vary as much as 20 to 25 percent on a single sample sent simultaneously to different labs.

The study results from Dr. Dudley’s team, in which 60 subjects’ samples were sent simultaneously out for 22 tests at to the three lab test companies, bore out that variability as well.

“We took the same person’s blood and split it and said it was different people,” Dr. Dudley said. “LabCorp and Quest had different results [on some tests] compared to Theranos — for the same person.”

“Theranos really didn’t look bad,” he said.

Fellow scientists and doctors who reviewed the data said Theranos looked better than they expected, given the shroud of secrecy around the company.

Theranos is so secretive about its lab work that Dudley was not even sure if Theranos had performed the tests in-house or had sent them out to Quest or Labcorp or any other lab for testing.

The Theranos results for the lipid panel — an important gauge of high cholesterol — was off more than others. Theranos’ tests yielded cholesterol levels an average of 9 percent lower than the other two companies’ results.

“Our results found that all of the lab tests had wide variability, and Theranos’ results were just a bit more off on the cholesterol,” he said. “It seemed to me to be something that would be entirely fixable.”

The media mostly skipped over how variable results can be across the entire industry and zoomed in on Theranos.

The Theranos backlash wasn’t limited to the media, either. A respected researcher was asked at a recent event what he would tell Elizabeth Holmes if he could.

“Go back to Stanford,” he said.

The culture of healthcare is, generally, at odds with the tech space in Silicon Valley.

The tech sector likes to keep its data private, but in healthcare, you are expected to publish it. The tech sector adheres to the “great man” myth. In the healthcare sector, there’s more appreciation for the hive mind.

If I had the chance to tell Elizabeth Holmes something, it might be that we need people who are pushing the outside of the envelope, and that – while things look bleak – I’m hoping she is yet able to deliver on some of the promise of the technology she has developed.

It would be a stunning turnaround. And who doesn’t love a good comeback?